For centuries, London’s social season revolved around debutantes. Yet in 1958, the final debutante curtseyed to Queen Elizabeth and the Duke of Edinburgh at court. The tradition that thousands of girls had gone through in order to officially “come out” into society was over. Gone were the presentation parties that had transformed from formal affairs requiring that girls wear a court dress with a train, carry a bouquet of flowers and a fan, and wear three feathers in their hair to less formal parties requiring mere day dresses.

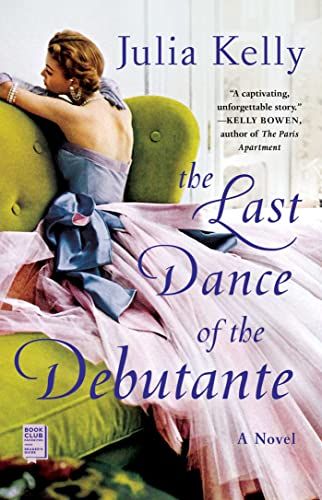

When, in 1957, it was announced that the following year would be the last Season for presentations, the palace was inundated with thousands of requests from eager mothers, aunts, and grandmothers wanting to present their eligible girls. I wrote a book about a debutante whose life changes forever because of the people she meets and events that unfold during the 1958 Season.

So, if so many women were trying to bring their girls to Buckingham Palace to curtsey to the Queen, why did it all end?

The origins of the debutante

The presentation of girls at court to the monarch is a tradition that started in Britain during the eighteenth century. (It's a custom at the center of the Netflix series Bridgerton) When an aristocratic girl became of age to marry, she would be brought to court by a sponsor—usually her mother or another older female relative—and presented to the monarch. Once this was done, she would be officially “out” on the marriage market.

For the duration of the Season, a girl would be invited to balls and parties in order to meet eligible, single men who she might then marry. In the 18th and 19th centuries, a girl would have been expected to secure an engagement in her first or second Season. If she did not, she risked being “put on the shelf” and faced the life of a spinster.

Who could be a debutante

By the time that 1958 rolled around, the rules around debutante presentations at court were set in stone. A girl could only be presented by a woman who herself had been presented, thus keeping the pool of debutantes restricted to a privileged few.

A debutante’s chaperone would apply to the palace for an invitation by writing to the Lord Chamberlain. He would then draw up a list of girls who would be offered invitations. Those invitations included the invitation itself and two cards that allowed the girls entry to the Ball Supper Room for their curtsey to the Queen and to the reception afterwards where they would be rejoined by their chaperon.

The exclusivity of requiring a chaperon who had herself been presented meant that some girls with great wealth but more modest family backgrounds would hire a professional chaperone to shepherd them through the season. In researching The Last Dance of the Debutante, I also found that divorced women would not be received at court, a restriction that showed the palace was way behind the times in a country where divorce was becoming more and more common.

A dying tradition

The answer to the question of why the tradition of debutante presentations at court stopped in 1958 is a multi-faceted one. The easiest explanation is that the monarchy wanted to distance itself from the practice.

Allegedly, the Duke of Edinburgh called Queen Charlotte’s Ball—one of the highlights of the debutante season where debutantes acted as handmaidens and curtseyed to a giant cake meant to represent the Queen Charlotte of the 18th century—as “bloody daft” and put an end to it being held at Buckingham Palace. (Actress Golda Rosheuvel plays a fictionalized version of the real-life Queen Charlotte on Bridgerton.)

Always one for a good quip or soundbite—especially the shocking ones—Princess Margaret is supposed to have looked around a debutante party and said, “They’re letting every tart in London in.”

Although I would call into serious question Princess Margaret’s slur against these girls, it is true that the debutante presentations had far more diplomats’, bankers’, and barristers’ daughters in their ranks than they did dukes’, earls’, and barons’ daughters. The British upper crust, devastated by two wars, had changed in the first half of the 20th century, so much so that an Edwardian would hardly recognize the Season’s parties.

However, an equally likely explanation for the demise of the debutante presentations is that the monarchy recognized that society was moving on. Queen Elizabeth began her reign with the first televised coronation. She was supposed to represent modernity in a Britain that had experienced incredible change in the years after World War II.

The final debutante presentations took place in 1958, just before the Swinging Sixties, second-wave feminism, and the sexual revolution would change British life forever. More opportunities were coming about for the girls who would be debutantes as well. Although university attendance was by no means commonplace for girls, doors were opening up. More and more girls also worked, including many of the previous years’ debutantes.

Debutantes after 1958

The Season and its focus on debutantes did not immediately stop because the palace put an end to presentations. The Season soldiered on for a few more years, with girls’ families continuing to hold coming out balls and parties to bring their daughters out into society. However, by the end of the 1960s and into the early 1970s, the practice was all but gone in Britain.

There has been an attempt to revive the Season in the 21st century, but the efforts have been very modest compared to what once was. In other places such as Vienna and the United States, the debutantes traditions unique to those places continue on. However, it seems unlikely that the British debutante will have her heyday again.

Julia Kelly is the author of books about ordinary women and their extraordinary stories. In addition to writing, she’s been an Emmy-nominated producer, journalist, marketing professional, and (for one summer) a tea waitress. Julia called Los Angeles, Iowa, and New York City home before settling in London. Readers can visit JuliaKellyWrites.com to learn more about all of her books and sign up for her newsletter so they never miss a new release.