Have you ever wondered why our universe is made up of something rather than nothing? It can hurt your brain if you think about it too much because if there were nothing you would have no brain—no you at all—to consider the question.

So let’s contemplate something simpler: why does the universe allow us to exist? Yet again, we run into the same problem: if the universe didn’t allow us to exist, we wouldn’t be here to think about it. This is called the “anthropic principle.” For some, it’s the only answer we need to explain, well, everything; but for others, it’s a philosophical thorn in the side. Everything we know about the universe so far—dating back to the 16th-century Polish astronomer Copernicus, who first proposed that Earth travels around the sun rather than the other way around—tells us that we have no special place in the cosmos. We are not at the center. This is the “Copernican principle.”

The anthropic and Copernican principles are conflicting axioms about the universe’s existence and our place within it. The anthropic principle says the universe depends on our being here. Meanwhile, the Copernican principle says that we are not special, and no law of physics should depend on our existence. Yet, the vast and ancient universe we see in our telescopes appears to balance both principles, like a pin balanced on the edge of a glass.

So why is our universe the way it is, and why do we exist as self-aware beings, tiny in size and minuscule in lifespan, relative to the lonely cosmic vastness mostly devoid of life? If the universe were made just for us, surely it would be small, human sized, perhaps just one planet or solar system or galaxy, not billions. Why should a universe made for us have black holes, for example? They seem to contribute nothing to our welfare.

Some scientists believe the universe wasn’t finely tuned to create intelligent life like us at all. Instead, they say, the universe evolved its own insurance policy by creating as many black holes as possible, which is the universe’s method of reproduction. Following this line of thinking, the universe itself may very well be alive—and the fact that we humans exist at all is just a happy side effect.

A Finely-Tuned Universe

One of the biggest philosophical problems with the universe is that it has to be finely tuned for us to even exist. If the universe were random, things would quickly become messy. If modified only a tiny bit one way or another, physical parameters such as the speed of light; the mass of the electron, proton, and neutron; the gravitational constant; and so on would eliminate all life—possibly all matter itself—and even the universe as a whole would not last long enough to evolve anything. For example, if their masses were slightly different, protons would decay into neutrons instead of the other way around, and as a result, there would be no atoms.

One possible solution to fine tuning is the multiverse. In this speculative theory, our universe is one of many in the same way that the planet Earth is one of many planets. Different universes have different laws of physics and, therefore, that ours supports life is simply a matter of luck. While some theories of the multiverse propose that these universes are essentially random and have no relationship to one another, one particular multiverse theory suggests that universes in fact reproduce like living beings and have ancestors and descendants. This theory is called cosmological natural selection (or CNS for short). First proposed by theoretical physicist Lee Smolin in 1992, the CNS theory is a strong contender for why our universe seems to balance both the Anthropic and Copernican principles.

When we look at the complexity of living things and the sheer number of non-living configurations there are, we’re left to assume that there’s no way species could appear randomly. Hence, some powerful being must have created all types of living creatures individually as a watchmaker builds a watch, the thinking often goes. However, Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution, which he first posited in his 1859 book, On the Origin of Species, provides a mechanism that explains why living things are non-random. Their parameters are not freely chosen; they are the product of natural selection, the process by which members of a species that are better fit to survive and/or reproduce more effectively are more likely to pass on their genes.

The theory of evolution is one of the greatest success stories in the history of science because it provided a mechanism by which a thing that is highly ordered, complex, and finely tuned for its survival could arise from natural processes. The theory was successful not only because it explained how species arise, but also because it generated new predictions that we could then test. For example, the theory of evolution explains why species appear related to one another.

The Beauty in Black Holes

The cosmological natural selection theory solves the pernicious problem of a universe finely tuned for life. That idea may make sense to us, living on a planet full of complex, multicellular organisms, but Earth is surrounded by mostly dead space and, as far as we know, dead planets, and moons and light years of interstellar dust and stray photons.

Earth is finely tuned for life; the universe is not. However, the cosmological natural selection theory says that the universe is finely tuned for something else: its method of reproduction, giving birth to new universes.

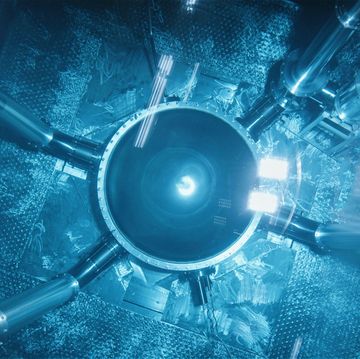

Under the CNS theory framework, every black hole becomes a baby universe. Our universe, likewise, started out as a black hole in its mother universe. The theory says that inside every black hole, the central singularity—which is matter highly compressed in space in the mother universe—becomes a highly compressed point in time in the new universe. This point expands, creating new matter and energy. You get a complete universe from even a tiny black hole.

This means that our universe is finely tuned not for life, but for black holes, which typically come from massive stars (although they can have other origins). It turns out that massive star formation depends on an element also important for life on Earth: carbon.

Carbon monoxide is the second-most common molecule in the universe after molecular hydrogen, even more common than water. In the molecular clouds of gas and dust that form from supernovae, massive stars coalesce amid gaseous carbon monoxide molecules, which act as a coolant. This cooling helps matter clump together and form the stars. Carbon is a critical component in all life that we know of. Therefore, life is, in fact, a byproduct of stellar formation, which is itself a byproduct of what the universe evolved to do: create as many black holes as possible.

The cosmological natural selection theory helps explain why our universe is so highly ordered, complex, and self-sustaining like Darwin’s theory explains the same for living things. That leads to the tantalizing, if speculative, conclusion that perhaps, by some definition, our universe itself is alive.

Dr. Tim Andersen is a principal research scientist at Georgia Tech Research Institute. He earned his doctorate in mathematics from Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute in Troy, New York, and his undergraduate degree from the University of Texas at Austin. He has published academic works in statistical mechanics, fluid dynamics (including a monograph on vortex filaments), quantum field theory, and general relativity. He is the author of The Infinite Universe on Medium and Stubstack and a book by the same name. He lives with his wife and two cats, and has a son and daughter at home as well as one grown son.