burningnightgiver asked:

Hello dears! I am asking you to support my campaign to help me reach my goal. I am now in bad need your support to help me stay alive and safe. Gaza is a very dangerous place either on the level of livelihood or on the level of souls. I need your monetary support to enable me to get the basic needs for my family till Rafah crossing point reopens to move my family to safety and peace. Please help a family be alive through your small donations or througn your shares to others. Thank you so Much for your stand beside people in need.

Help this family

Watching Przewalski’s horses run free on the Kazakhstan steppe for the first time in 200 years

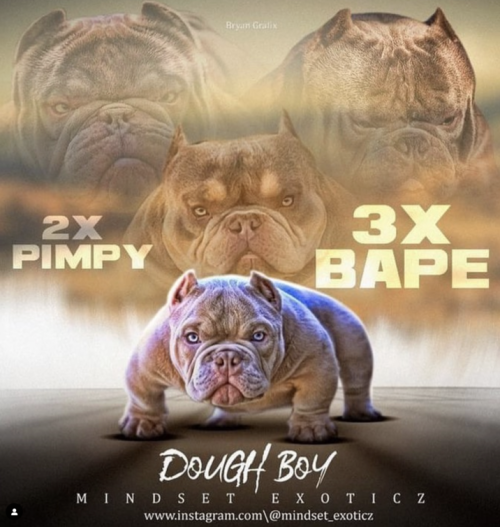

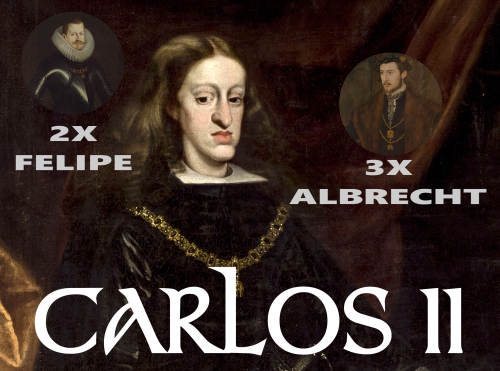

thinking about 2x pimpy 3x bape

Tip of the iceberg, really. Don’t worry, it’s even worse than this implies

ancient gene reactivated

Congratulations, you’ve reinvented Lystrosaurus

(via velociraptrix)

Anonymous asked:

I've seen people say that saber-toothed cats couldn't roar because only Panthera felids can today. But if other large carnivorans like bears and pinnipeds could evolve the ability to roar independently, I don't see why saber-toothed cats would be any different. (Even if it would've sounded different from their modern cousins.)

“Roar” is so vaguely defined a term as to be almost nonscientific. What people mean when they say “saber-toothed cats couldn’t roar” is referring to a specific vocalization in big cats - this deep, long-distance territorial call. It has a distinct pattern in each species, and between individuals:

These cats have two specializations that make them able to do this. First, they have an incompletely ossified hyoid - the epihyoid is replaced by a ligament. This allows for the larynx to retract deeper into the throat, making the vocalizations deeper and louder. Incidentally, this also means that they can’t purr like small cats do. The second adaptation is that the vocal folds within the larynx are really thick, which lowers the pitch even further.

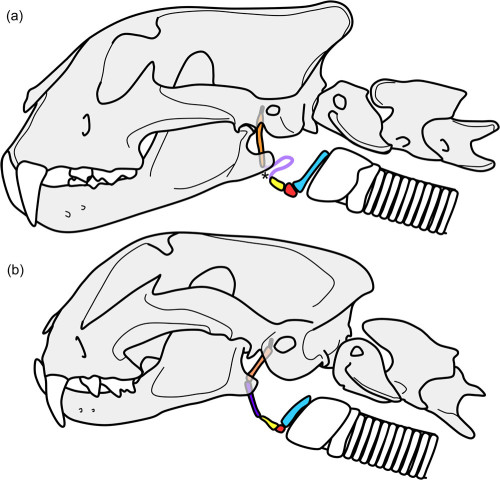

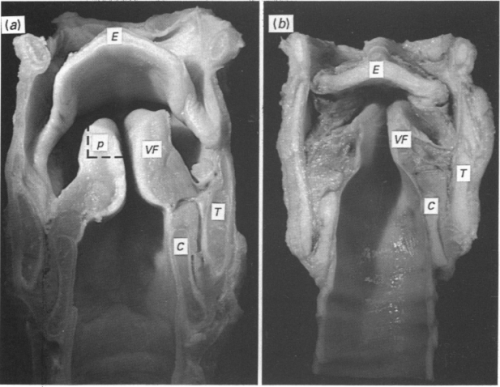

Left: the hyoids of a roaring tiger (A) and a non-roaring caracal (B); from Deutsch et al. 2023. Right: the larynxes of a roaring jaguar (A) and non-roaring snow leopard (B); from Hast 1989.

Snow leopards have an incompletely ossified hyoid (which means they can’t purr), but they don’t have the thickened vocal folds. They make the exact same long-distance territorial call as the other members of Panthera, but it instead sounds like this:

Clouded leopards have neither of these specializations, and they basically just meow like a small cat:

So what of saber-toothed cats? Hyoid elements are known from Smilodon. Their shape resembles those of small cats, implying that the larynx itself had a similar morphology (i.e., without the thick vocal folds of big cats). However, the hyoids are also significantly bigger than those of any living cats - including big cats. This implies that the larynx itself was proportionally bigger, and that would mean a deeper pitch to the vocalizations. No modern cat has a disproportionately increased larynx like that, but male Mongolian gazelles and hammer-headed bats have larynxes at least twice the size of the females’, and consequently make deeper calls (unfortunately I couldn’t find good recordings of either online). The fact that Smilodon is also just larger animal would mean its vocalizations would be deeper than those of small cats anyways. However, the lack of laryngeal specializations means that it may not have had the same deep formant frequencies as big cats; this means the sound would have been less resonant and maybe not able to travel as far.

So basically, Smilodon may have been able to “roar”, but not the same roar as modern big cats. Rather, it’d be like the calls of small cats, but much deeper in pitch. A baritone meow, if you will.

Who is markiplier

Speaking of saber-toothed cat vocalizations, random trivia: since 1973, the Denver Museum of Nature and Science has had a bust of a Smilodon in the foyer. It’s a donation box, and you drop coins into its throat.

When you drop a coin into its throat, it plays this yowling roar sound. It was made using the same synths they had to make the soundtracks for the planetarium shows. It’s clearly electronic, but it sounds really cool:

Anonymous asked:

I've seen people say that saber-toothed cats couldn't roar because only Panthera felids can today. But if other large carnivorans like bears and pinnipeds could evolve the ability to roar independently, I don't see why saber-toothed cats would be any different. (Even if it would've sounded different from their modern cousins.)

“Roar” is so vaguely defined a term as to be almost nonscientific. What people mean when they say “saber-toothed cats couldn’t roar” is referring to a specific vocalization in big cats - this deep, long-distance territorial call. It has a distinct pattern in each species, and between individuals:

These cats have two specializations that make them able to do this. First, they have an incompletely ossified hyoid - the epihyoid is replaced by a ligament. This allows for the larynx to retract deeper into the throat, making the vocalizations deeper and louder. Incidentally, this also means that they can’t purr like small cats do. The second adaptation is that the vocal folds within the larynx are really thick, which lowers the pitch even further.

Left: the hyoids of a roaring tiger (A) and a non-roaring caracal (B); from Deutsch et al. 2023. Right: the larynxes of a roaring jaguar (A) and non-roaring snow leopard (B); from Hast 1989.

Snow leopards have an incompletely ossified hyoid (which means they can’t purr), but they don’t have the thickened vocal folds. They make the exact same long-distance territorial call as the other members of Panthera, but it instead sounds like this:

Clouded leopards have neither of these specializations, and they basically just meow like a small cat:

So what of saber-toothed cats? Hyoid elements are known from Smilodon. Their shape resembles those of small cats, implying that the larynx itself had a similar morphology (i.e., without the thick vocal folds of big cats). However, the hyoids are also significantly bigger than those of any living cats - including big cats. This implies that the larynx itself was proportionally bigger, and that would mean a deeper pitch to the vocalizations. No modern cat has a disproportionately increased larynx like that, but male Mongolian gazelles and hammer-headed bats have larynxes at least twice the size of the females’, and consequently make deeper calls (unfortunately I couldn’t find good recordings of either online). The fact that Smilodon is also just larger animal would mean its vocalizations would be deeper than those of small cats anyways. However, the lack of laryngeal specializations means that it may not have had the same deep formant frequencies as big cats; this means the sound would have been less resonant and maybe not able to travel as far.

So basically, Smilodon may have been able to “roar”, but not the same roar as modern big cats. Rather, it’d be like the calls of small cats, but much deeper in pitch. A baritone meow, if you will.

But then around 30 million years ago — halfway through the Age of Mammals, give or take — something happened. The nautiloids started disappearing. Fewer species, less diversity. Bit by bit they shrank back into their current small range.

What happened halfway through the Age of Mammals? Well, here’s one clue: the nautiloids’ long retreat showed a pattern. It wasn’t everywhere and all at once. They disappeared first in the northern arctic regions; then in the Antarctic; then in temperate zones; finally across most of the tropics except that one small patch. This pattern suggested a culprit: a warm-blooded predator that evolved in the Arctic and then spread around the world.

But… the armored cephalopod design had been around forever. They’d been living with predators for half a billion years. Sharks. Primitive armored fish. Not-so-primitive modern fish. In the age of dinosaurs, they had to deal with ichthyosaurs, plesiosaurs, and mosasaurs. Back in the Paleozoic, they were hunted by eight-foot-long giant sea scorpions. Way back in the Cambrian, they had to live with the anomalocariids. In the early Age of Mammals, there were primitive whales and sea-going crocodiles. The armored cephalopod design took them all in stride and kept going.

So what happened?obsessed with this photo. the face of a slurper

The ability of mammals to create vacuum chambers in their mouth – universal due to the necessity of sucking milk during infancy – is a very useful, and very unappreciated one. Something as simple as sipping water from a cup would be impossible if not for all the layers of soft, wriggly flesh built on top of our jaws.

I recall some book recounting how mammals turned their face inside-out during our evolution in the latest Paleozoic – reptiles and bird mostly have their head and jaw muscle inside their skulls, mammals mostly have them outside. This also allows us to have complex facial expressions, which are vital for mammalian communication, and only exist because of milk.

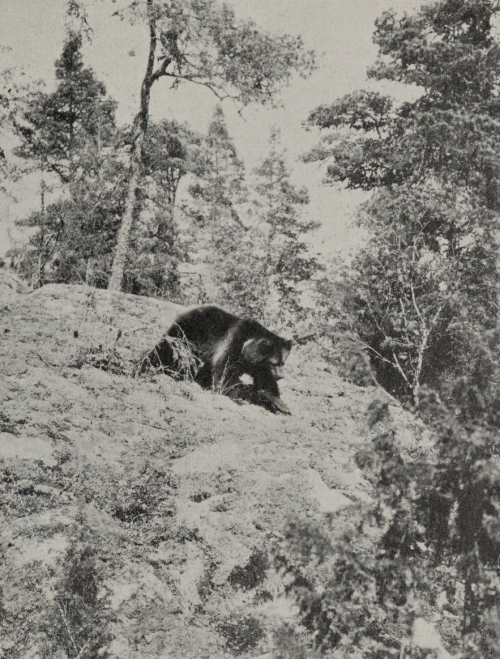

Swedish brown bear

By: Eric von Rosen

From: Lebensbilder aus der Tierwelt

1908