To keep fish and shrimp healthy, farmers in Indonesia now have a copilot to help

Read this story in Bahasa Indonesia.

JATIMALANG VILLAGE, Indonesia – It’s just after sunrise and shrimp farmer Andriyono is perched on a thin bamboo walkway over one of his 16 ponds on the southern coast of Central Java.

With a rope, he gently pulls a flat circular net out of the water, along with a dozen leaping shrimp. He is checking for leftover feed. Satisfied there is none, he lowers the net back into the dark water.

Feed residue can indicate poor appetite in shrimp, which can stem from anything from disease to not enough oxygen in the water or too high of a pH reading. The residue itself is also bad for water quality, leading to a vicious spiral. Left unchecked, it could result in sick or dead shrimp within days.

Shrimp are sensitive creatures.

“If one shrimp gets a virus, the whole pond of shrimp will die,” said Elsa Vinietta, Head of Aquaculture Platform and AI for eFishery, an aquatech startup whose aim is to modernize aquaculture. Disease can spread when a bird drinks from one pond then another or from simply flowing water from one infected pond to another.

When a farm is well-managed though, that can boost shrimp survival rates from as low as 60 percent to as high as 90 percent, said Vinietta.

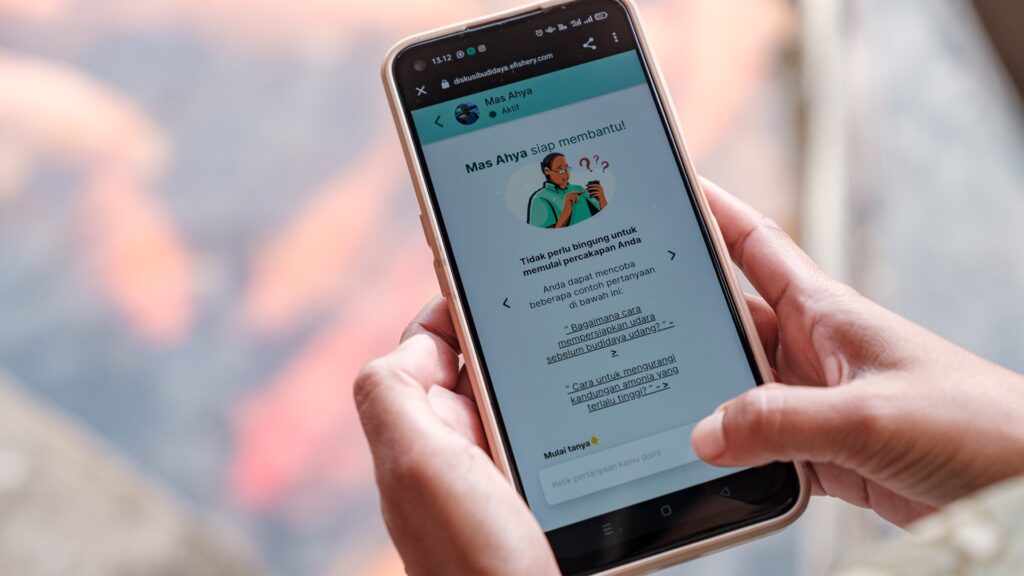

Recently, Andriyono started using a generative AI assistant, called Mas Ahya, to help keep his shrimp healthy. Mas is “Mr.” and Ahya is a combination of ahli (expert) and budidaya (cultivate). Accessed via a mobile app, Mas Ahya is a pilot project by eFishery to scale up access to aquaculture expertise using Microsoft Azure OpenAI Service.

Andriyono made a switch 10 years ago from growing rice to farming shrimp. He now makes five times what he used to.

In the month of February alone, he asked Mas Ahya a wide range of questions in Javanese – like, “What is the quality of my pond water?” to “What is the condition of the plankton?” to “What is the market price of shrimp?”

“Since using Mas Ahya, I know every second what the quality of the water is. I can also estimate prices better,” said Andriyono, 39. “Mas Ahya makes everything quicker.”

Aquaculture boom

Half of the world’s seafood now comes from aquaculture, the aquatic equivalent to agriculture. In 2020, of the 178 million tonnes (196 million tons) of seafood produced globally, 51 percent was caught in seas and lakes and 49 percent bred through aquaculture, according to a report published in 2022 by the United Nations’ Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO).

Indonesia is the third-largest aquaculture producer (seven percent of global share), after China (35 percent) and India (eight percent). The Indonesian government has ambitious targets for expanding the sector further but as is the case elsewhere, environmental degradation is a serious concern, leading to calls for more sustainable farming methods.

eFishery was founded in 2013 by Gibran Huzaifah, a former catfish farmer who had built his own Internet of Things (IoT)-based automated feeder to overcome a common problem – the over and under feeding of fish. Overfeeding wastes money and under feeding results in undersized fish.

Bandung-based eFishery’s mission is to modernize traditional fish and shrimp farming, raising yields to help meet growing world demand for protein. It now serves 200,000 farmers and is valued at $1.4 billion USD, having secured funding from some of the region’s biggest sovereign and venture capital funds.

eFishery offers financing for feed and infrastructure where farmers pay after harvest. It also collects data from its automated eFeeders and water quality monitoring system and presents them as charts on its eFarm mobile app. To interpret those charts though, many farmers rely on an eFishery aquaculture technician who visits as often as twice weekly to answer questions.

Last year, eFishery began using Azure IoT to connect and communicate with its eFeeders and water quality monitors, gathering and analyzing data in real time.

It also developed Mas Ahya using Azure OpenAI Service as a generative AI tool for farmers to get this data – and insights – as well as draw on eFishery’s proprietary expertise and best practices. Farmers can ask questions and get answers in plainspoken language and have this expertise in their hands anytime to maximize production.

Azure OpenAI Service’s local language capabilities – Mas Ahya is currently available in Bahasa Indonesia, Javanese and English – was a big draw. “This will lower the barrier to entry even further for our farmers,” said Andri Yadi, eFishery’s VP of AIoT & Cultivation Intelligence.

“Anytime, anywhere”

In the village of Paremono about an hour’s drive northwest of Yogyakarta, Ira Nasihatul Husna farms tilapia with her husband. They have the only fish farm in the village and their 10 ponds are fringed by coconut trees and rice fields.

Tilapia is a white fish, popular because it’s not very bony. Ira and her husband Purwanto sell cleaned and gutted fish to local restaurants.

She used to scatter feed by hand three times a day, an inexact endeavor. “If you feed too much, it’s a waste,” she said. “Too little and the harvest size is not maximal and you get less money.”

The ponds draw water from a river and the big challenge is maintaining water quality. In the rainy season, for example, ammonia levels go up and Ira has to add a supplement to bring it down.

Last year, they installed an eFeeder and more recently a water quality monitor connected to the eFarm app. More precise feeding and more even spreading of the feed has shortened the time from fry to market size from four to three-and-a-half months. The automated feeding has also freed Ira up to do other things like pick her child up from school.

In February, Ira began piloting Mas Ahya. She can now check on water quality and feeds and immediately get solutions if there’s a problem. She said it’s given her the ability to “access information anytime, anywhere, outside of working hours.”

One recent question she had for Mas Ahya: How do you overcome fungus in tilapia? Answer: Add quicklime – or calcium oxide – to reduce acidity in the water. Mas Ahya included dosage instructions.

Ira said she would like to expand her farm, as local demand is more than she can fulfill.

As for Andriyono, the shrimp farmer, he and his team used to do four manual feedings a day. The eFeeder now scatters feed continuously throughout the day, from 6am to 6pm. The shrimp grow faster when they eat small amounts often.

Andriyono used to send water samples to the local lab and wait two days for the results. Now, in addition to manually checking for excess feed with a net in the morning, he can ask Mas Ahya what the state of each pond is.

Mas Ahya provides data from the water quality monitors – pH, oxygen, temperature and salinity levels – which allows the farmer to quickly respond to the most life-threatening parameters. It also integrates lab data – more than 100 parameters including bacteria, plankton and ammonia levels – so farmers can get in-depth analysis that can inform longer-term practices, so they are more sustainable.

Andriyono exports the biggest shrimp and sells the rest locally. Since he got the eFeeder, 40 percent of his shrimp now go for export, compared to 30 percent before. He thinks Mas Ahya can help improve his yield further.

“My plan is to export all since it is higher value,” he said.

Sustainability goals

A future goal for eFishery is to help Indonesian fish and shrimp farmers adopt more sustainable practices and help them get certified locally and by global organizations such as US-based Best Aquaculture Practices (BAP) and Seafood Watch.

Mas Ahya will also play a role in this, providing information on why sustainability is important and how certification can open new markets, said Vinietta. This includes pointing out shortcomings and giving detailed instructions on the best infrastructure and practices, such as treating wastewater from ponds before releasing it into the environment.

The team is also looking at supporting image, video and other formats on Mas Ahya beyond simple text, possibly using Azure OpenAI Service GPT-4 Turbo with Vision, said Vinietta.

The focus on sustainability and technology is making aquaculture appealing to a new generation.

“Young people want to join the eFishery movement,” said Romi Witjaksono, the 24-year-old product manager for Mas Ahya. “It’s a nice meeting point where you combine IT with fish.”

Top image: Andriyono, a shrimp farmer, checks for leftover feed in one of his shrimp ponds. Photo by Fauzy Chaniago for Microsoft.