Net neutrality—the idea that internet service providers should treat all traffic equally—might seem quaint during the Covid-19 pandemic. Internet traffic is surging, so why not tap the brakes on entertainment or porn to make sure people can access schoolwork, health care information, and apply for unemployment?

But who should decide which internet services deserve special treatment? Maybe Zoom and other video conferencing apps should get priority, since they’re used for remote work, telehealth, and education. But people also use them for socializing and games. Or maybe providers should throttle streaming video services like Netflix and YouTube. But those services can be used in education too, not to mention keeping up with current events.

Rather than rendering net neutrality obsolete, the Covid-19 crisis reminds us why it’s such an important principle. More people than ever rely on the internet, and they should be free to choose the video conferencing tools, education sites, or entertainment they want, rather than let broadband providers decide for them—or sell priority to the highest bidder. The crisis shows that even in dire circumstances, internet companies can provide a neutral network.

In December 2017, the Republican-controlled Federal Communications Commission jettisoned rules that banned internet providers from blocking, throttling, or otherwise discriminating against lawful content. The order also reversed the Obama-era FCC's decision to classify broadband internet providers as "Title II" common carriers, similar to traditional telephone companies, leaving the agency with less authority to regulate broadband providers during emergencies like the pandemic.

Net neutrality opponents claimed that regulating internet providers like telephone companies had hurt broadband infrastructure investment and that dropping the rules would spur more investment. Other critics warned that broadband providers needed to be able to prioritize certain types of content to prevent internet slowdowns. The experience of the past few months suggests those arguments were overstated, at best.

Broadband providers and network infrastructure companies report that internet traffic surged by anywhere between 10 percent and 40 percent between February and March amid layoffs, school closures, and shelter in place orders. Video accounted for a huge part of the increases. Nokia's network analytics company Deepfield reported Netflix traffic increases of 54 percent to 75 percent in some places in between mid-February and mid-March. Netflix said its traffic hit an all-time high in March. Teleconferencing, meanwhile, saw a 300 percent increase in Deepfield's analysis and online gaming saw 400 percent growth during the same period.

This spike in entertainment traffic is the sort of situation that net neutrality opponents worried about. For example, during an FCC hearing on overturning the net neutrality rules in 2017, Republican commissioner Michael O'Rielly fretted that entertainment content could overwhelm networks, to the detriment of more important traffic. "I, for one, see great value in the prioritization of telemedicine and autonomous car technology over cat videos," O’Rielly said at the time.

That was a specious argument. The 2015 rules allowed carriers to carry critical data by bypassing the public internet entirely. But it turns out prioritization wasn't even necessary. Data gathered by internet analysis company Ookla shows that any slowing of internet speeds in recent months has been localized, and slight. Speeds generally have remained at or above the speeds during the December 2019 holiday season, and home broadband speeds are now increasing, according to Ookla's data. These are averages, so that means some providers could be struggling more than others and that certain neighborhoods or towns might not hold up as well as others, but on the whole, networks in the US have held up well.

Comcast and Charter, the two largest cable broadband providers in the US, kept average internet speeds fairly steady despite the surge of gaming and video, without throttling major streaming video services, according to preliminary data from researchers at Northeastern University. The researchers distribute an app, called Wehe, that anyone can download to test whether their internet provider is throttling data. Researcher David Choffnes says the group didn't see any significant changes in March or April.

Some net neutrality critics argue that US networks can only keep up with the deluge of video traffic because broadband providers invested more money in their networks since the FCC repealed the Obama-era rules. But some major broadband providers have actually cut spending during the period.

Last year Comcast reduced its capital expenditures for its cable division, including for costs associated with expanding into new areas and scaling existing infrastructure, to $6.9 billion, from $7.7 billion in 2018. Likewise, Charter said it cut capital expenditures to $7.2 billion last year, from $9.1 billion in 2018. AT&T said it would spend $3 billion less in 2020. AT&T declined to comment. Charter and Comcast did not respond to requests for comment.

Broadband providers tend to plan network upgrades years in advance. That’s probably why several providers, including Comcast, increased their infrastructure spending after the 2015 net neutrality rules were passed. A study published last year by researchers at George Washington University concluded that the FCC's net neutrality rules "had no impact on telecommunication industry investment levels" between 2015 and 2017.

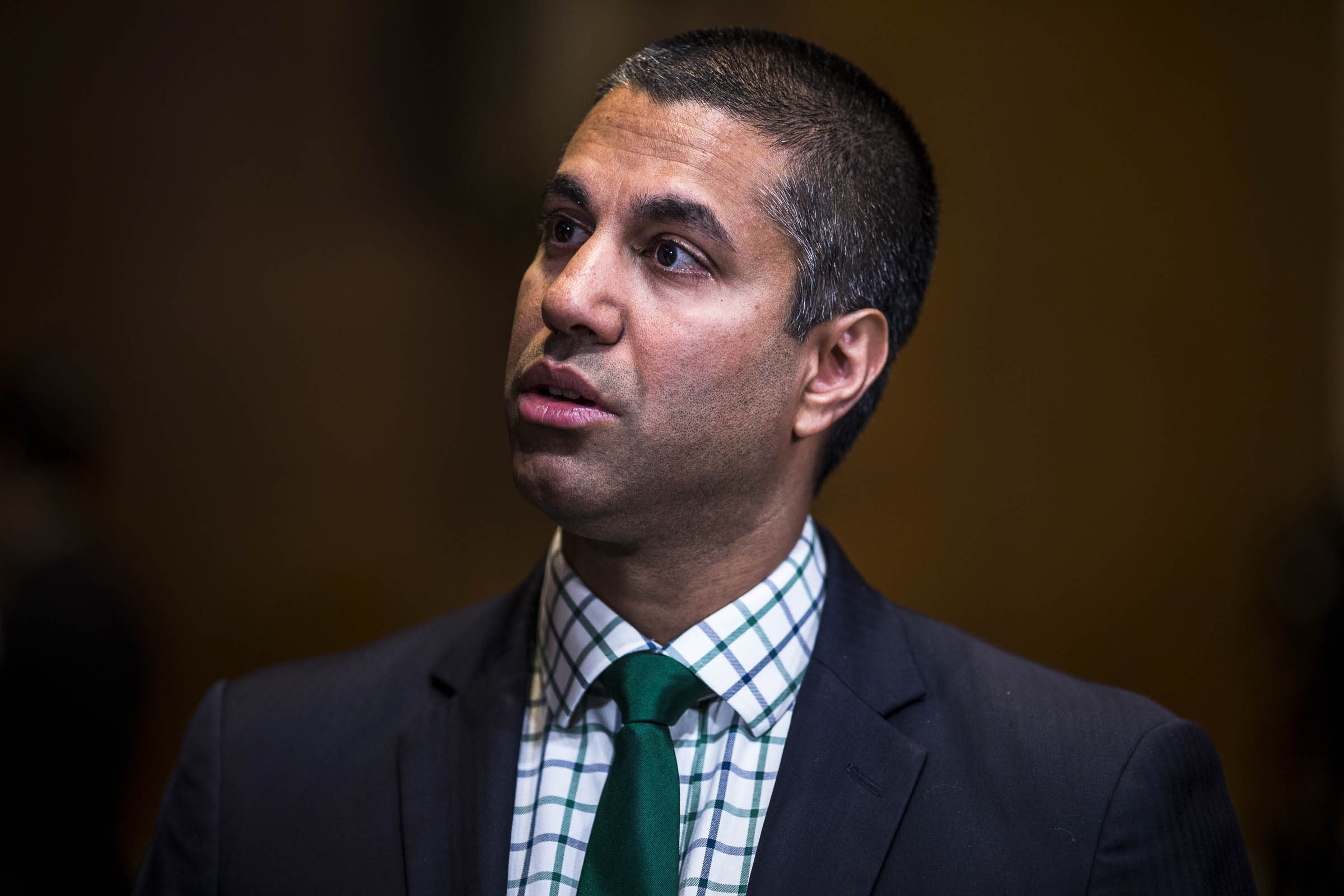

It would be tempting to call the FCC’s changes a wash. The investments in infrastructure that Chair Ajit Pai promised haven't materialized, while carriers don't yet appear to be throttling connections any more than they were before. But the pandemic underscores just how important the internet is and what happens when people don't have it. Internet is an essential public service. But with the exception of a few publicly owned broadband providers, carriers are obligated to serve investors, not the public interest. By repealing the common carrier rule, the FCC gave up much of its authority to police the behavior of broadband carriers during times of crisis. Among other things, the 2015 rules prohibited "unjust or unreasonable prices and practices." The FCC did not respond to a request for comment.

Critics say the 2017 changes left the FCC with less authority to ensure that everyone can access the internet during the pandemic. The FCC says more than 700 companies and organizations have signed its "Keep American Connected" pledge not to terminate internet service over pandemic-related financial troubles, to waive late fees, and to allow free access to certain Wi-Fi services.

But critics say the FCC can't force internet providers to honor those commitments. The public is left to rely on the goodwill of for-profit companies. The most vulnerable in society will pay the price, notes Harold Feld of the advocacy group Public Knowledge. "If you're folks who are dependent on the low-income access program and the ISP is not living up to its promises, you're not going to get much help and support," he says.

- How a doomed porpoise may save other animals from extinction

- Wait, what’s the deal with sunscreen? Does it work or not?

- The ultimate quarantine self-care guide

- Anyone's a celebrity streamer with this open source app

- The face mask debate reveals a scientific double standard

- 👁 AI uncovers a potential Covid-19 treatment. Plus: Get the latest AI news

- 💻 Upgrade your work game with our Gear team’s favorite laptops, keyboards, typing alternatives, and noise-canceling headphones