An artificial intelligence watchdog should be set up to make sure people are not discriminated against by the automated computer systems making important decisions about their lives, say experts.

The rise of artificial intelligence (AI) has led to an explosion in the number of algorithms that are used by employers, banks, police forces and others, but the systems can, and do, make bad decisions that seriously impact people’s lives. But because technology companies are so secretive about how their algorithms work – to prevent other firms from copying them – they rarely disclose any detailed information about how AIs have made particular decisions.

In a new report, Sandra Wachter, Brent Mittelstadt, and Luciano Floridi, a research team at the Alan Turing Institute in London and the University of Oxford, call for a trusted third party body that can investigate AI decisions for people who believe they have been discriminated against.

“What we’d like to see is a trusted third party, perhaps a regulatory or supervisory body, that would have the power to scrutinise and audit algorithms, so they could go in and see whether the system is actually transparent and fair,” said Wachter.

It is not a new problem. Back in the 1980s, an algorithm used to sift student applications at St George’s Hospital Medial School in London was found to discriminate against women and people with non-European-looking names. More recently, a veteran American Airlines pilot described how he had been detained at airports on 80 separate occasions after an algorithm repeatedly confused him with an IRA leader. Others to fall foul of AI errors have lost their jobs, had car licences revoked, been kicked off the electoral register or mistakenly chased for child support bills.

People who find themselves on the wrong end of a flawed AI can challenge the decision under national laws – but the report finds that the current laws to protect people are not now effective enough.

In Britain, the Data Protection Act allows automated decisions to be challenged. But UK firms, in common with those in other countries, do not have to release any information they consider a trade secret. In practice, this means that instead of releasing a full explanation for a specific AI decision, a company can simply describe how the algorithm works. For example, a person turned down for a credit card might be told that the algorithm took their credit history, age, and postcode into account, but not learn why their application was rejected.

In 2018, European member states, along with Britain, will adopt new legislation that governs how AIs can be challenged. Early drafts of the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) enshrined what is called a “right to explanation” in law. But the authors argue that the final version approved last year contains no legal guarantee.

“There is an idea that the GDPR will deliver accountability and transparency for AI, but that’s not at all guaranteed. It all depends on how it is interpreted in the future by national and European courts,” Mittelstadt said. The best the new regulation offers is a “right to be informed” compelling companies to reveal the purpose of an algorithm, the kinds of data it draws on to make its decisions, and other basic information. In their paper, the researchers argue for the regulation to be amended to make the “right to explanation” legally binding.

“We are already too dependent on algorithms to give up the right to question their decisions,” said Floridi. “The GDPR should be improved to ensure that such a right is fully and unambiguously supported”.

For the study, the authors reviewed legal cases in Austria and Germany which have some of the stricter laws around decision-taking algorithms. In many cases, they found that courts required companies to release only the most general information about the decisions algorithms had made. “They didn’t need to disclose any details about the algorithm itself and no details whatsoever about your individual decision or how it was reached based on your data,” Wachter said. A trusted third party, she added, could balance companies’ concerns over trade secrets with the right for people to be satisfied that a decision had been reached fairly. “If the algorithms can really affect people’s lives, we need some kind of scrutiny so we can see how an algorithm actually reached a decision,” she added.

But even if a AI watchdog were set up, it may find it hard to police algorithms. “It’s not entirely clear how to properly equip a watchdog to do the job, simply because we are often talking about very complex systems that are unpredictable, change over time and are difficult to understand, even for the teams developing them,” Mittelstadt said. He adds that forcing companies to ensure their AIs can explain themselves could trigger protests, because some modern AI methods, such as deep learning, are “fundamentally inscrutable.”

Alan Winfield, professor of robot ethics at the University of the West of England, is heading up a project to develop industry standards for AIs that aims to make them transparent and so more accountable. “A watchdog is a very good proposal,” he said. “This is not a future problem, it’s here and now.”

But he agreed that tech firms might struggle to explain their AI’s decisions. Algorithms, especially those based on deep learning techniques, can be so opaque that it is practically impossible to explain how they reach decisions. “My challenge to the likes of Google’s DeepMind is to invent a deep learning system that can explain itself,” Winfield said. “It could be hard, but for heaven’s sake, there are some pretty bright people working on these systems.”

Nick Diakopoulos, a computer scientist at the University of Maryland, said that decisions taken by algorithms will need to be explained in different ways depending on what they do. When a self-driving car crashes, for example, it makes sense for the algorithm to explain its decisions to crash investigators, in the same way air traffic investigators have access to aircraft black boxes, he said. But when an algorithm is used in court to advise a judge on sentencing, it may make sense for the judge, the defendant and their legal team to know how the AI arrived at its decision.

“I think it is essential to have some kind of regulatory body with legal teeth that can compel transparency around a set of decisions that have led to some kind of error or crash,” Diakopoulos said.

When AI goes awry

Sarah Wysocki, a school teacher in Washington DC, received rave reviews from her students’ parents and her principal. But when the city introduced an algorithm in 2009 to assess teacher performance, she and 205 others scored badly and were fired. It turned out that the program had based its decisions on tiny numbers of students’ results, and that some other teachers had apparently fooled the system by advising their students to cheat. The school could not explain why excellent teachers had been sacked.

Beauty contest organisers used an algorithm to judge an international event last year. They thought the software would be more objective than humans and pick a winner based on facial symmetry, a lack of wrinkles and other possible measures of beauty. But the system had been trained predominantly on white women and discriminated against dark skin.

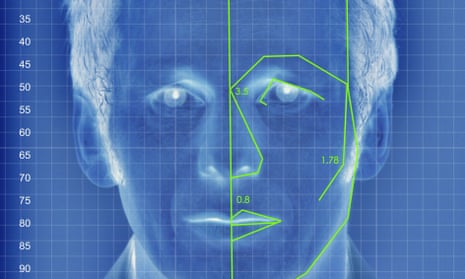

John Gass, a resident of Natick, Massachusetts, had his driving licence revoked when an antiterrorism facial recognition system mistook him for another driver. It took him ten days to convince authorities that he was who he said he was. He had never been convicted of any driving offences.

Microsoft’s Tay chatbot was created to strike up conversations with millennials on Twitter. The algorithm had been designed to learn how to mimic others by copying their speech. But within 24 hours of being let loose on the internet, it had been led astray, and became a genocide-supporting, anti-feminist Nazi, tweeting messages such as “HITLER DID NOTHING WRONG.”

An automated system designed to catch dads who were not keeping up with childcare payments targeted hundreds of innocent men in Los Angeles who had to pay up or prove their innocence. One man, Walter Vollmer, was sent a bill for more than $200,000. His wife thought he had been leading a secret life and became suicidal.

More than 1000 people a week are mistakenly flagged up as terrorists by algorithms used at airports. One man, an American Airlines pilot, was detained 80 times over the course of a year because his name was similar to that of an IRA leader.

A 22-year-old Asian DJ was denied a New Zealand passport last year because the automated system that processed his photograph decided that he had his eyes closed. But he was not too put out. “It was a robot, no hard feelings. I got my passport renewed in the end,” he told Reuters.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion