Listen to this article

Produced by ElevenLabs and News Over Audio (NOA) using AI narration.

Bernie the spectacled bear is one of the star attractions at Chester Zoo in the north of England. He is also one of Brexit’s forgotten losers.

Since Britain left the European Union, zoos have struggled to take part in breeding swaps designed to help vulnerable and endangered species, and Bernie has been waiting for two years for the correct paperwork allowing him to move to Germany and romance a female bear. “Prior to Brexit, this would have been in place in 6-8 weeks,” the zoo’s spokesperson told me by email.

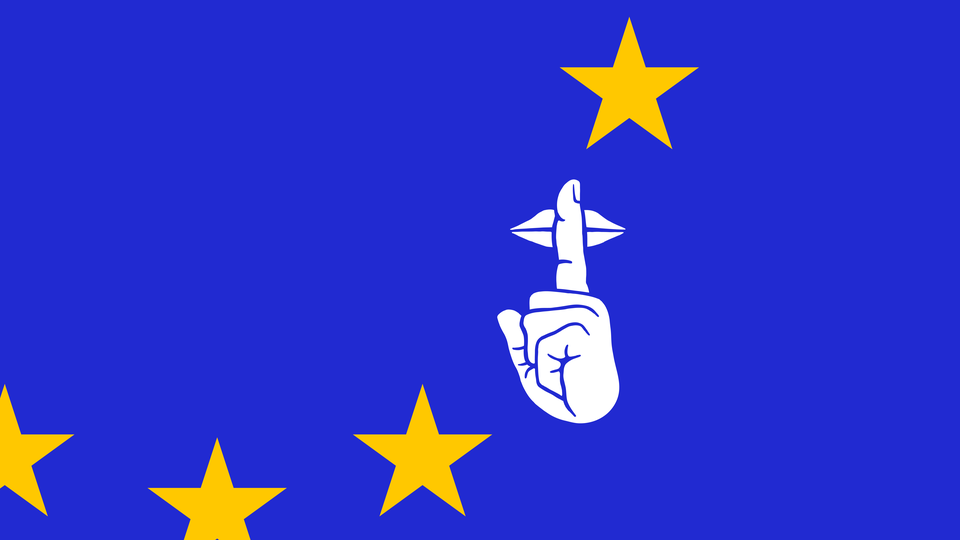

The plight of hundreds of zoo animals in the country is a reminder of how comprehensively Brexit reshaped the United Kingdom’s relationship with the continent across the Channel. And yet the B-word has barely featured in the campaign to choose the next Westminster government on July 4—not in the debates between party leaders, nor in the policy measures briefed to friendly newspapers, nor in the leaflets sent out by individual candidates. The Conservative Party manifesto is a whopping 80 pages long, but uses the word Brexit only 12 times. The word does not even appear as a stand-alone section of the Labour platform, instead falling under the wider heading of “Britain reconnected.”

Champions and opponents of Brexit alike have decided that now isn’t the time to talk about this enormous change to Britain’s place in the world. Nigel Farage, the man who led the populist campaign to leave the European Union, rebranded his UK Independence Party as the Brexit Party for the 2019 election. Now, however, his political vehicle is called simply Reform, and he would rather talk about small boats crossing the Channel or the perils of a cashless society. Even the Liberal Democrats, a pro-European party that campaigned the last time around on a pledge to rejoin the EU (and went from 12 to 11 seats as a result), now claim that this is only a “longer-term objective.”

As someone who has worked in journalism in Britain for nearly two decades, I can tell you: This is an extraordinary turnaround. During the first half of my career, the campaign to leave the European Union was an obsession of the Conservative right, to the extent that the Tory leader at the time, David Cameron, urged his party to stop “banging on about Europe.” Then came the 2016 referendum, in which Brexit was hailed as a populist triumph against the elite consensus and a foreshadowing of Donald Trump’s election in the U.S. that November. That was followed by three bitter, tedious years of bickering in Parliament over the terms of Britain’s exit, as it became apparent that populist victories are more easily won than put into practice. By December 2019, the process had dragged on for so long that Boris Johnson won an 80-seat majority for the Conservatives by promising simply to “get Brexit done.” And he did: Britain left the European Union—including its single market and customs union—in January 2020.

Mission accomplished! Success at last! A promise delivered! And yet four years later, the Tories, now led by Rishi Sunak, are getting exactly zero credit for delivering their signature policy and laying to rest their obsession of the past two decades. The Conservatives are now so far behind in the polls—and so fearful of a wipeout on the scale of that suffered by the mainstream right-wing party in Canada’s 1993 election—that they have switched from trying to win the election to trying to lose less badly. This week, one Tory minister urged voters to back the Conservatives in order to avoid giving Labour a “supermajority,” a term used in reference to the U.S. Congress that doesn’t even mean anything in the British political system. Despite having delivered Brexit exactly as they promised, the Conservatives don’t just fear defeat on July 4. They fear annihilation.

What happened? Quite simply, Brexit has been a bust. Conservative ministers like to talk up the trade deals they have signed with non-European countries, but no normal voter cares about pork markets. Anyone who voted for Brexit to reduce immigration will have been severely disappointed: Net migration was 335,000 in 2016, but rose to 685,000 last year, down from a record high of 784,000 in 2022. And although the economic effects of leaving the European single market were blurred by the pandemic and the energy shock that followed Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, one can safely say that Britons do not feel richer than they did four years ago.

Above all, voters are bored with Brexit. In April 2019, according to the pollster Ipsos, 72 percent of Britons rated Brexit as one of the most important issues facing the country. Today that figure is 3 percent. “The one thing we found in focus groups that unites Leave and Remain voters is that they don’t want to talk about it,” Anand Menon, the director of the independent think tank UK in a Changing Europe, told me. “Brexiters think the Tories have screwed it up. Labour don’t want to mention it because [Keir] Starmer is vulnerable.”

That point about Starmer is crucial. Before the 2019 election, he was Labour’s shadow Brexit spokesperson—and showed sympathy to the party’s membership, which leaned heavily toward Remain. But when he became Labour leader the next year—following Johnson’s crushing victory—Starmer accepted that Brexit had to happen, and he ordered his party to vote it through Parliament. In the current election, polls suggest that Labour is winning over many Leave voters who supported the Conservatives in 2019. The last thing those switchers want to hear is backsliding on Europe. And so the Labour manifesto promises to “make Brexit work” with no return to the single market, customs union, or freedom of movement.

The B-word has featured more heavily in debates in Scotland, where the majority of voters backed Remain and the governing Scottish National Party is keen to outflank Labour. It is also an election issue in Northern Ireland, where the status of the border with the Republic of Ireland is still fraught. But with both major parties in England extremely reluctant to mention Brexit, the media here have largely followed suit. One of the few exceptions is Boris Johnson, the former prime minister now reborn as a tabloid-newspaper columnist, who accused Starmer of plotting to rejoin the single market. Using a Yiddish word meaning “mooch,” Johnson asserted that “if Schnorrer gets in, he will immediately begin the process of robbing this country of its newfound independence … until this country is effectively locked in the legislative dungeon of Brussels like some orange ball-chewing gimp.” (The infamous hostage scene in Quentin Tarantino’s film Pulp Fiction apparently made a strong impression on Johnson.)

Johnson might be deploying his usual rhetorical exuberance and cultural insensitivity, but he does have a point. The next government will have many decisions to make about how to manage Britain’s relationship with the EU. The current wall of silence “will all change after the election,” Menon said. “You will get a load more noise about it from Labour members.” Businesses unhappy with post-Brexit import and export regulations “will dare to be more vocal under a Labour government,” he predicted. The trouble is that minor tinkering might help some of the minor problems created by Brexit—Labour has indicated that it will look at the regulations keeping Bernie and other zoo animals from fulfilling their duty to preserve endangered species—but only rejoining the single market would bring dramatic economic benefits. And doing that would involve exactly the trade-off with British sovereignty that Brexiteers campaigned against for so long. Hard conversations can be postponed, but usually not forever. That’s bad news for the 97 percent of Britons who are enjoying the respite from years of arguments over Britain’s relationship with Europe.

For now, though, the political consequences of Brexit fatigue are most pronounced on the right. Leaving the EU has created many modest irritations—see Bernie the bear’s love life—without delivering the large rewards that were promised. Here is a lesson for populists everywhere, one that the U.S. anti-abortion lobby has learned since Roe v. Wade was overturned: Don’t be the dog that catches the car.