Spatial access to healthcare facilities refers to how long people need to travel to reach care. Any barriers in access increase the likelihood that care will be delayed or completely forgone [1], which puts patients at risk of adverse health outcomes [2]. Ensuring timely access to healthcare is therefore a public health policy priority and a focal point in the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals. However, because spatial access is hard to measure directly, most research so far has focused on theoretical (potential) travel times [3]. These potential travel times do not account for travel delays or other factors experienced during actual visits, which can lead to underestimating travel times.

In “Revealed versus potential spatial accessibility of healthcare and changing patterns during the COVID-19 pandemic”, we developed an approach that leverages travel times to healthcare facilities from aggregated and anonymized data. We paint a complete picture of access by estimating the (revealed) travel time to medical facilities and contrast revealed travel times in the real world with potential travel times estimated using the Google Maps Platform Directions API, the same API that powers navigation in Google Maps.

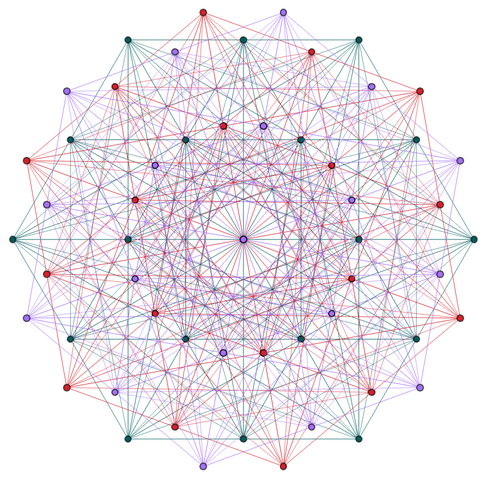

We then directly compare revealed to potential travel times across different modes of transportation to generate novel insights. First, we produce novel estimates of access to healthcare in over 100 countries, showing large gaps between optimal access estimates and real-world conditions. Specifically, revealed travel time differs substantially from potential travel time; in all but 4 countries this difference exceeds 30 minutes, and in 49 countries it exceeds 60 minutes (see Figure 1 below).

Second, this method allowed us to establish that the COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated existing inequalities on spatial access to healthcare facilities around the globe. This effect was especially pronounced for populations dependent on public transportation, who already needed a longer time to reach healthcare facilities pre-COVID-19. On average, typical trips to healthcare around the world by public transport increased by 18%, which amounts to around four additional minutes (illustrated in Figure 2 below, absolute change maps).

In conjunction with other relevant data, these findings provide a resource to help public health policymakers identify underserved populations and promote health equity by formulating policies and directing resources towards areas and populations most in need. For example, via a dashboard incorporating some of these methods and in collaboration with the OnTIME Consortium, we aim to reduce maternal deaths in Nigeria by identifying areas without adequate access to emergency obstetrics care and opportunities to shorten the time to reach existing facilities.

In summary, our new approach reveals substantial spatial and temporal disparities in access within and across countries. These results capture substantial changes in healthcare accessibility as the COVID-19 pandemic unfolded, and indicate that these changes were not distributed equally across populations within countries. Our insights are an important step towards enabling a greater understanding of barriers to care for the global population. Finally, we hope that future research using carefully anonymized real world data and further improved privacy-preserving methods can help measure what is happening in reality and help improve public health efforts around the globe.

References

- Buzza C, Ono SS, Turvey C, Wittrock S, Noble M, Reddy G, Kaboli PJ, Reisinger HS. Distance is relative: unpacking a principal barrier in rural healthcare. J Gen Intern Med. 2011 Nov;26 Suppl 2(Suppl 2):648-54. doi: 10.1007/s11606-011-1762-1. PMID: 21989617; PMCID: PMC3191222. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21989617/

- Jablonski KA, Guagliardo MF. Pediatric appendicitis rupture rate: a national indicator of disparities in healthcare access. Popul Health Metr. 2005 May 4;3(1):4. doi: 10.1186/1478-7954-3-4. PMID: 15871740; PMCID: PMC1156944. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15871740/

- Weiss DJ, Nelson A, Vargas-Ruiz CA, Gligorić K, Bavadekar S, Gabrilovich E, Bertozzi-Villa A, Rozier J, Gibson HS, Shekel T, Kamath C, Lieber A, Schulman K, Shao Y, Qarkaxhija V, Nandi AK, Keddie SH, Rumisha S, Amratia P, Arambepola R, Chestnutt EG, Millar JJ, Symons TL, Cameron E, Battle KE, Bhatt S, Gething PW. Global maps of travel time to healthcare facilities. Nat Med. 2020 Dec;26(12):1835-1838. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-1059-1. Epub 2020 Sep 28. PMID: 32989313. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32989313/

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in