On Cairo’s dying trams

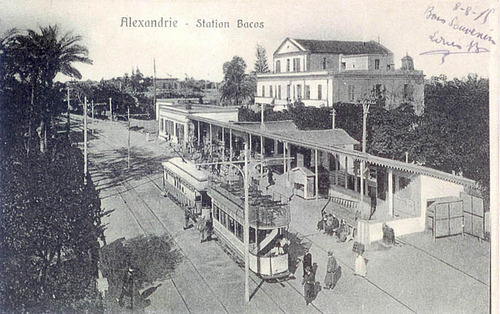

[Top: surviving tram linking Cairo’s central station with the suburb of Heliopolis. Bottom: Tram in Alexandria at Bacos station, 1910s]

It has been ten years since Al-Ahram Weekly published a piece by Amira El-Noshokaty about Cairo’s (and Egypt’s) dying trams (May 2002). Trams were first installed in Alexandria then Cairo and other cities in the delta at the end of the 19th century. The system was neglected from the early 1970s then was faced with top-down decisions made by the state regarding the role of the private (imported) car in the future of Egyptian cities. Anwar Sadat was an Americanizer, which hasn’t turned out to be a good thing for the average urban Egyptian. In his memoirs he wrote that he dreamt for every Egyptian to own a car, a house and a television set. In typical dictatorial fashion and without making decisions based on studies, public interest or the opinions of planners and experts, Sadat favored the removal of Cairo’s extensive tram network, which he saw as obstacles to the imported Ford and Chevrolet cars. During his decade of rule, Cairo lost over half of its 120 kilometers of trams and tracks but his dream was never realized as reality was far more complex than his stubborn naive vision. Central Cairo was left without its much needed trams, however the trams in the suburbs of Heliopolis and Helwan were still intact.

The remaining trams are merely functional. There is no maintenance, upgrading, investments, utilization of advertising space, modernizing of stations, and obviously no expansion of the remaining network. Streets in Masr el Gedida/Heliopolis clogged with cars while the middle of the road, where the tracks are, sits empty with no trams passing for over an hour. While this should inspire car owners to think “what would my commute be like if these tracks were used efficiently with a well-run tram running on schedule?” the typical response has been inspired by Sadatist thinking “what would my commute be like if we removed those tracks and made an extra lane.”

The Helwan network, equally neglected, has been thoroughly taken off life support as the cables needed to electrify the trains from above, were stolen during last year’s security vacuum. The tram was becoming so ineffective that when the opportunity came, someone thought the cables were worth more than the public service provided by the system.

[Alexandria tram at Ramleh Station]

There is still an opportunity in Cairo, and Alexandria where some tracks continue to exist to invest in upgrading the trams. A $100 million loan/investment can transform Cairo’s Heliopolis/Nasr City system in ways that will have felt impact on mobility, ease traffic, and with proper ticketing and advertising generate income to pay back the loan/investment.

Here is Al-Ahram Weekly’s tram piece from a decade ago:

End of the line?

Once an efficient mainstay of public transport, Cairo’s tram is being branded today as passé. Amira El-Noshokaty takes a ride

When I was a college student the tram provided the perfect ride, slow enough to give me and my friends time to gossip and cheap enough for our pockets. Besides, it was the only vehicle that actually moved on Salah Salem during the rush hour. Life would slip pleasantly by our open windows as we rode the faded red-and-yellow- striped car from Nasr city to Abbasiya, squinting at the tiny digits on the pink tickets. It never crossed our minds that we were riding a little piece of urban history.

“The tram started work in 1910, linking Heliopolis to the rest of Cairo. Until 1992, it was managed by the Heliopolis Company, and then it came under the authority of the Cairo Transportation Authority,” Effat Badr, head of the Heliopolis metro service, told Al-Ahram Weekly. According to Andre Raymond’s Le Caire, the tramway public transport network in the greater Cairo area was designed between 1894 to 1917. On December 1894, Baron Empain – the man who built modern Heliopolis – was granted the contract to build a transport network for Cairo. In the first phase, eight tram lines were laid, six running from Al-Attaba Al-Khadra. With the exception of a line running through Mohamed Ali Street, the old city was excluded from the network.

Recounting the effect of this dramatic development on the Cairenes, Gamal Badawi, in his book Egypt: from the window of history, says: “On the first day of August in 1896, the houses of Cairo became empty. People rushed, women, men and children, to the street and crowded on the length of the road from Bulaq to the Citadel through Attaba Al-Khadra Square to see that strange creature, running on smooth tracks with children hanging on its back fender screaming, "The effrit! The effrit!” Badawi claims that the first ride was taken by the Minister of Infrastructure of the time, Hussein Fakhry Pasha, and quotes the daily Muqattam newspaper as having reported that: “It speeds to race with the wind… in a scene not witnessed by any of the peoples of the East.”

The system was then extended in 1917 to include 22 new lines, a few of which even extended across the Nile into Imbaba and Giza. But then the motorcar arrived and eroded business.

Today, as Badr points out, “the metro” refers to both the tram and the metro. The tram, established in 1900, is older and slower, the car not exceeding 18km per hour. The newer metro can, on occasion, move at 28km per hour. Each tram car has a capacity of 96 passengers while each metro car can carry 144 people.

In its heyday, the tram serviced downtown Cairo, Shubra, Sayeda Zeinab and Helwan. But to ease traffic congestion, the trams and their overhead conductors have been removed from Shubra and Sayeda Zeinab. In 1992, in an attempt to modernise the network, trams were introduced on to the metro lines, bringing the total number of both metro and tram cars in Cairo to 37 and carrying an estimated 100,000 passengers per day.

But slowly the system is being dismantled. As part of the Cairo governorate’s urban renewal plan, the tramway was pulled out of Al-Galaa Street in 1998 and there are plans to strip the network from parts of Salah Salem Street.

The original intention was to dismantle and transfer the system to less developed governorates. But last February, when a fatal accident occurred on the Heliopolis line, the press threw doubt on the quality and efficiency of the metro. Local newspapers cited frequent power cuts, broken motors and lack of spare parts as the cause of several accidents.

In defence of the tram, Badr argues that it has a good record. “There are daily check-ups on both metro and tram cars and there is also an annual and bi-annual maintenance programme,” she says. However, stranded trams are still a common sight on the streets of Cairo.

“While the tram is cheap, it is also very old and terribly slow,” Shubra resident Zeinab Mohamed says. She regularly travels to Heliopolis to buy medication, but usually takes a taxi costing about LE8 – a substantial sum compared with a 25 or 50-piastre tram ticket. But when she runs short of money the tram is her only choice.

As the car rumbled on, I remembered the old story about the rural simpleton who came to Cairo and was swindled into buying a tram. His cousins were sold the Pyramids and Al-Attaba Al- Khadra Square. In those days, the tram was impressive – an object of admiration, like the pyramids or the Cairo Tower – and no one could conceive of selling it.

But today, who would buy it?

[tram in Giza linking Cairo to the pyramids via Al-Ahram Street]

UPDATE (November 15, 2012)

[photo of a tram fire in Heliopolis on November 14. Image circulating social networks shows not only inadequate maintenance and lack of modernization of the system but also the state’s inability to respond to emergencies]

8 notes

eman-gamal liked this

eman-gamal liked this elhelwy liked this

moussakaspace liked this

languidsoul reblogged this from cairobserver

dfrezh liked this

fshoukry liked this

cairobserver posted this